John Chrysotom Once Again She Calls for Johns Head

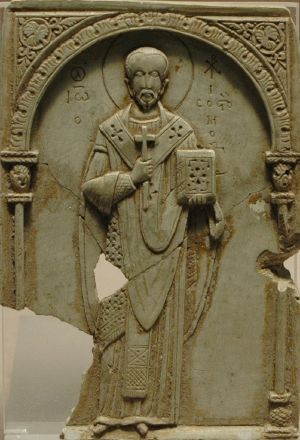

| Saint John Chrysostom | |

|---|---|

| A millennium-former Byzantine mosaic of Saint John Chrysostom, Hagia Sophia | |

| Bishop and Md of the Church | |

| Born | 349 in Antioch |

| Died | September fourteen, ca. 407[ane] in Comana in Pontus [1] |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church building, Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Catholic Churches, Anglican Communion, Lutheran Church |

| Banquet | November thirteen (Eastern Orthodox Church), September thirteen (Roman Catholic Church) |

| Attributes | represented in art by bees, a dove, a pan [ii] |

| Patronage | Constantinople; epilepsy; lecturers; orators; preachers [3] |

John Chrysostom (349– ca. 407 C.E.) was the archbishop of Constantinople known for his eloquence in preaching and public speaking, his denunciation of abuse of authority by both ecclesiastical and political leaders, and his ascetic sensibilities. After his death he was given the Greek surname chrysostomos, "golden mouthed," rendered in English language as Chrysostom.[2] [1]

The Orthodox Church and Eastern Catholic Churches honour him equally a saint (feast day, November xiii) and count him amid the Three Holy Hierarchs (banquet day, January 30), together with Saints Basil the Not bad and Gregory the Theologian. He is recognized past the Roman Catholic Church building as a saint and a Medico of the Church. Churches of the Western tradition, including the Roman Catholic Church, the Church of England, and the Lutheran church, commemorate him on September 13. His relics were looted from Constantinople by Crusaders in 1204 and brought to Rome, but were returned on 27 November 2004 by Pope John Paul 2.[3]

Chrysostom is known inside Christianity chiefly equally a preacher and liturgist, peculiarly in the Eastern Orthodox Church building. Outside the Christian tradition Chrysostom is noted for eight of his sermons which played a considerable part in the history of Christian antisemitism, and were extensively used by the Nazis in their ideological campaign confronting the Jews.[4] [five]

Contents

- 1 Biography

- ane.1 Early life and education

- 1.ii Priesthood and service in Antioch

- 1.3 Patriarch of Constantinople

- 2 Writings

- 2.1 Homilies

- 2.two Treatises

- 2.3 Sermons on Jews and Judaizing Christians

- 2.4 Liturgy

- three Legacy and influence

- iii.1 Influence on the catechism and clergy

- 3.2 Antisemitism

- three.three Music and literature

- 3.4 Collected works

- four Notes

- 5 References

- 6 External links

- 7 Credits

He is sometimes referred to as John of Antioch, but that name more than properly refers to the bishop of Antioch named John (429-441), who led a group of moderate Eastern bishops in the Nestorian controversy. He is too dislocated with Dio Chrysostom.

Biography

Early life and educational activity

John, later called "golden rima oris" (Chrysostom), was born in Antioch in 349.[half dozen] [7] Different scholars draw his mother as a pagan[viii] or as a Christian, and his male parent was a loftier ranking military officer.[ix] John'due south father died soon after his birth and he was raised by his mother. He was baptised in 368 or 373 and installed as a reader (one of the modest orders of the Church).[10] As a event of his mother's influential connections in the city, John began his education under the pagan teacher Libanius. From Libanius John acquired the skills for a career in rhetoric, besides as a love of the Greek linguistic communication and literature.[11] As he grew older, nonetheless, he became more deeply committed to Christianity and went on to written report theology nether Diodore of Tarsus (1 of the leaders of the afterwards Antiochian school). Co-ordinate to the Christian historian Sozomen, Libanius was supposed to accept said on his deathbed that John would have been his successor "if the Christians had not taken him from the states."[12] He lived as an ascetic and became a hermit circa 375; he spent the side by side two years continually standing, scarcely sleeping, and committing the Bible to memory. As a consequence of these practices, his tummy and kidneys were permanently damaged and poor wellness forced him to return to Antioch.[13]

Priesthood and service in Antioch

He was ordained as a deacon in 381 past Saint Meletius of Antioch, and was ordained as a presbyter (another word for priest) in 386 past Bishop Flavian I of Antioch. Over the course of 12 years, he gained popularity because of the eloquence of his public speaking, especially his insightful expositions of Bible passages and moral teaching. The almost valuable of his works from this period are his Homilies on diverse books of the Bible. He emphasised charitable giving and was concerned with the spiritual and temporal needs of the poor. He as well spoke out against abuse of wealth and personal property:

Practice you lot wish to honour the body of Christ? Practice not ignore him when he is naked. Do not pay him homage in the temple clad in silk, only then to neglect him exterior where he is cold and ill-clad. He who said: "This is my torso" is the aforementioned who said: "Y'all saw me hungry and you gave me no food," and "Whatsoever y'all did to the least of my brothers you did also to me"... What adept is it if the Eucharistic tabular array is overloaded with gilt chalices when your blood brother is dying of hunger? Start by satisfying his hunger and and so with what is left y'all may adorn the chantry equally well.[14]

His straightforward understanding of the Scriptures (in contrast to the Alexandrian trend towards allegorical interpretation) meant that the themes of his talks were practical, explaining the Bible'south application to everyday life. Such straightforward preaching helped Chrysostom to garner popular support. He founded a series of hospitals in Constantinople to care for the poor.[15]

One incident that happened during his service in Antioch illustrates the influence of his sermons. When Chrysostom arrived in Antioch, the bishop of the city had to intervene with Emperor Theodosius I on behalf of citizens who had gone on a rampage mutilating statues of the Emperor and his family unit. During the weeks of Lent in 397, John preached 21 sermons in which he entreated the people to run into the mistake of their ways. These made a lasting impression on the general population of the city: many pagans converted to Christianity as a result of the sermons. As a result, Theodosius' vengeance was not as severe as it might have been.[xvi]

Patriarch of Constantinople

In 398 C.Eastward., John was requested—against his will—to take the position of Patriarch of Constantinople. He deplored the fact that Imperial court protocol would at present assign to him admission to privileges greater than the highest country officials. During his time every bit bishop he doggedly refused to host lavish social gatherings, which made him popular with the common people, simply unpopular with wealthy citizens and the clergy. His reforms of the clergy were also unpopular with these groups. He told visiting regional preachers to return to the churches they were meant to be serving—without any payout.[17]

His time in Constantinople was more than tumultuous than his time in Antioch. Theophilus, the Patriarch of Alexandria, wanted to bring Constantinople under his sway and opposed John's appointment to Constantinople. Being an opponent of Origen's teachings, he accused John of being as well partial to the teachings of that theologian. Theophilus had disciplined iv Egyptian monks (known as "the tall brothers") over their support of Origen'due south teachings. They fled to and were welcomed past John. He made another enemy in Aelia Eudoxia, the wife of the eastern Emperor Arcadius, who assumed (perhaps with justification) that his denunciations of extravagance in feminine apparel were aimed at herself.[16]

Depending on one'south outlook, John was either tactless or fearless when denouncing offences in high places. An brotherhood was soon formed against him by Eudoxia, Theophilus and others of his enemies. They held a synod in 403 to charge John, in which his connection to Origen was used confronting him. It resulted in his deposition and banishment. He was called back by Arcadius almost immediately, every bit the people became "tumultuous" over his departure.[18] In that location was likewise an earthquake the night of his arrest, which Eudoxia took for a sign of God's anger, prompting her to ask Arcadius for John'southward reinstatement.[19] Peace was short-lived. A silver statue of Eudoxia was erected almost his cathedral. John denounced the dedication ceremonies. He spoke confronting her in harsh terms: "Again Herodias raves; once again she is troubled; she dances again; and again desires to receive John's head in a charger,"[xx] an allusion to the events surrounding the death of John the Baptist. Once over again he was banished, this time to the Caucasus in Armenia.[21]

Pope Innocent I protested at this banishment, only to no avail. John wrote letters that nonetheless held great influence in Constantinople. As a result of this, he was further exiled to Pitiunt (Abkhazia region of Georgia) where his tomb is a shrine for pilgrims. He never reached this destination, equally he died during the journeying. His last words are said to have been, "Glory to God for all things!"[19]

Writings

Homilies

Known as "the greatest preacher in the early church," John's sermons take been i of his greatest lasting legacies.[22] Chrysostom'south extant homiletical works are vast, including many hundreds of exegetical sermons on both the New Testament (especially the works of Saint Paul) and the Old Testament (especially on Genesis). Among his extant exegetical works are threescore-7 homilies on Genesis, fifty-nine on the Psalms, ninety on the Gospel of Matthew, lxxx-eight on the Gospel of John, and fifty-five on the Acts of the Apostles.[i]

The sermons were written down by the audition and subsequently circulated, revealing a style that tended to be direct and greatly personal, merely was also formed by the rhetorical conventions of his time and place.[23] In general, his homiletical theology displays many characteristics of the Antiochian school (i.due east., somewhat more literal in interpreting Biblical events), simply he also uses a good deal of the emblematic interpretation associated with the Alexandrian school.[1]

John's social and religious world was formed by the continuing and pervasive presence of paganism in the life of the city. 1 of his regular topics was the paganism in the civilisation of Constantinople, and in his sermons he thundered against popular pagan amusements: the theatre, horseraces, and the revelry surrounding holidays.[24] He specially criticized Christians for taking part in such activities:

"If you inquire [Christians] who is Amos or Obadiah, how many apostles at that place were or prophets, they stand mute; merely if you ask them well-nigh the horses or drivers, they answer with more solemnity than sophists or rhetors".[25]

One of the recurring features of John's sermons is his emphasis on treat the needy.[26] Echoing themes found in the Gospel of Matthew, he calls upon the rich to lay aside materialism in favor of helping the poor, often employing all of his rhetorical skills to shame wealthy people to abandon conspicuous consumption:

"Do you pay such honor to your excrements as to receive them into a silver chamber-pot when another man made in the prototype of God is perishing in the cold?"[27]

Treatises

Outside of his sermons, a number of John's other treatises have had a lasting influence. Ane such work is John'due south early treatise Against Those Who Oppose the Monastic Life, written while he was a deacon (quondam before 386), which was directed to parents, heathen as well every bit Christian, whose sons were contemplating a monastic vocation. The book is a sharp set on on the values of Antiochene upper-grade urban society written past someone who was a member of that class.[28] Chrysostom also writes that, already in his day, information technology was customary for Antiochenes to send their sons to be educated by monks.[29] Other important treatises written past John include On the Priesthood (one of his earlier works), Instructions to Catechumens, and On the Incomprehensibility of the Divine Nature.[thirty] In improver, he wrote a serial of well-known messages to the deaconess Olympias.

Sermons on Jews and Judaizing Christians

During his start two years as a presbyter in Antioch (386-387), Chrysostom denounced Jews and Judaizing Christians in a series of 8 sermons delivered to Christians in his congregation who were taking part in Jewish festivals and other Jewish observances.[31] Information technology is disputed whether the primary target were specifically Judaizers or Jews in general. His homilies were expressed in the conventional manner, utilizing the uncompromising rhetorical class known every bit the psogos, whose literary conventions were to vilify opponents in an uncompromising manner.

I of the purposes of these homilies was to prevent Christians from participating in Jewish community, and thus preclude the erosion of Chrysostom's congregation. In his sermons, Chrysostom criticized those "Judaizing Christians," who were participating in Jewish festivals and taking part in other Jewish observances, such as the shabbat, submitted to circumcision and fabricated pilgrimage to Jewish holy places.[32] Chrysostom claimed that on the shabbats and Jewish festivals, the synagogues were full of Christians, especially women, who loved the solemnity of the Jewish liturgy, enjoyed listening to the Shofar on Rosh Hashanah, and applauded famous preachers in accord with the contemporary custom.[33] A recent theory is that he instead tried to persuade Jewish Christians, who for centuries had kept connections with Jews and Judaism, to cull between Judaism and Christianity.[34]

Chrysostom held Jews responsible for the crucifixion of Jesus and added that they continued to rejoice in Jesus'south death.[35] He compared the synagogue to a pagan temple, representing it as the source of all vices and heresies.[36] He described it as a place worse than a brothel and a drinking shop; it was a den of scoundrels, the repair of wild beasts, a temple of demons, the refuge of brigands and debauchees, and the cavern of devils, a criminal assembly of the assassins of Christ.[iv] Palladius, Chrysostom'due south contemporary biographer, likewise recorded his merits that among the Jews the priesthood may exist purchased and sold for money.[37] Finally, he declared that he hated the synagogue and the Jews.[iv]

In Greek, the sermons are called Kata Ioudaiōn (Κατά Ιουδαίων), which is translated equally Adversus Judaeos in Latin and Against the Jews in English.[38] The most recent scholarly translations, claiming that Chrysostom'southward chief targets were members of his own congregation who connected to observe the Jewish feasts and fasts, requite the sermons the title Against Judaizing Christians. The original Benedictine editor of the homilies, Montfaucon, gives the following footnote to the championship: "A discourse against the Jews; only information technology was delivered confronting those who were Judaizing and keeping the fasts with them [the Jews]."[39] Every bit such, some take claimed that the original title misrepresents the contents of the discourses, which show that Chrysostom'due south primary targets were members of his own congregation who connected to discover the Jewish feasts and fasts. Sir Henry Savile, in his 1612 edition of Homilies 27 of Volume 6 (which is Discourse I in Patrologia Graeca's Adversus Iudaeos), gives the title: "Chrysostom's Discourse Against Those Who Are Judaizing and Observing Their Fasts."<r]."[39]

Liturgy

Beyond his preaching, the other lasting legacy of John is is influence on Christian liturgy. Two of his writings are particularly notable. He harmonized the liturgical life of the Church past revising the prayers and rubrics of the Divine Liturgy, or celebration of the Holy Eucharist. To this day, Eastern Orthodox and almost Eastern Catholic Churches typically celebrate the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom. These same churches also read his Catechetical Homily at every Easter, the greatest feast of the church year.

Legacy and influence

The Chrysostom Monastery in Moscow (1882).

During a fourth dimension when city clergy were discipline to criticism for their high lifestyle, John was determined to reform his clergy in Constantinople. These efforts were met with resistance and express success. He was an splendid preacher. Every bit a theologian, he has been and continues to be very important in Eastern Christianity, and is more often than not considered the nigh prominent doctor of the Greek Church, but has been less important to Western Christianity. His writings take survived to the present day more and so than whatsoever of the other Greek Fathers.[one] He rejected the gimmicky tendency for allegory, instead speaking evidently and applying Bible passages and lessons to everyday life.

His exiles demonstrated that secular powers dominated the Eastern Church at this period in history. It likewise demonstrated the rivalry betwixt Constantinople and Alexandria for recognition equally the preeminent Eastern See. Meanwhile in the westward, Rome's primacy had been unquestioned from the fourth century onwards. An interesting point to note in the wider development of the Papacy is that Innocent'southward protests had not helped, demonstrating the lack of secular influence the Bishops of Rome held in the east at this time.

Influence on the canon and clergy

Chrysostom's influence on church teachings is interwoven throughout the current Catechism of the Catholic Church building (revised 1992). The Catechism cites him in eighteen sections, peculiarly his reflections on the purpose of prayer and the meaning of the Lord'south Prayer:

- Consider how [Jesus Christ] teaches us to be humble, by making us encounter that our virtue does not depend on our piece of work alone but on grace from on loftier. He commands each of the faithful who prays to exercise so universally, for the whole world. For he did not say "thy will exist done in me or in us," but "on earth," the whole earth, so that error may be banished from it, truth have root in it, all vice be destroyed on it, virtue flourish on it, and world no longer differ from heaven.[40]

Christian clerics, such equally R.Southward. Storr, refer to Chrysostom equally "one of the near eloquent preachers who ever since churchly times take brought to men the divine tidings of truth and love," and the nineteenth century John Henry Cardinal Newman described Chrysostom as a "vivid, cheerful, gentle soul; a sensitive heart."[41]

Antisemitism

Chrysostom'south Adversus Judaeos homilies have been circulated past many groups to foster anti-Semitism.[4] James Parkes called the writing on Jews "the well-nigh horrible and violent denunciations of Judaism to be found in the writings of a Christian theologian".[42] His sermons gave momentum to the accusation of deicide—the thought that Jews are collectively responsible for the death of Jesus.[43] British historian Paul Johnson claimed that Chrysostom's homilies "became the design for anti-Jewish tirades, making the fullest possible use (and misuse) of fundamental passages in the gospels of St Matthew and John. Thus a specifically Christian anti-Semitism, presenting the Jews equally murderers of Christ, was grafted on to the seething mass of pagan smears and rumours, and Jewish communities were now at take a chance in every Christian city."[44] During World State of war II, the Nazi Party in Deutschland abused his piece of work in an attempt to legitimize the Holocaust in the eyes of German language and Austrian Christians. His works were oft quoted and reprinted equally a witness for the prosecution.[four]

Later World War II, the Christian churches denounced Nazi use of Chrysostom'southward works, explaining his words with reference to the historical context. According to Laqueur, it was argued that in the fourth century, the general discourse was brutal and aggressive and that at the fourth dimension when the Christian church building was fighting for survival and recognition, mercy and forgiveness were not in demand.[4] Co-ordinate to Patristics' scholars, opposition to any particular view during the late quaternary century was conventionally expressed in a manner, utilizing the rhetorical course known every bit the psogos, whose literary conventions were to vilify opponents in an uncompromising manner; thus, it has been argued that to call Chrysostom an "anti-Semite" is to employ anachronistic terminology in a way incongruous with historical context and record.[45]

Music and literature

Chrysostom's liturgical legacy has inspired several musical compositions. Noteworthy among these are: Sergei Rachmaninoff's Liturgy of St John Chrysostom, Op. 31, composed in 1910, one of his ii major unaccompanied choral works; Pyotr Tchaikovsky's Liturgy of St John Chrysostom, Op.41; and Arvo Part's Litany, which sets vii judgement prayers of Chrysostom's Divine Liturgy for chorus and orchestra.

James Joyce's novel Ulysses includes a grapheme named Mulligan who brings 'Chrysostomos' into some other character's mind because Mulligan's gold-stopped teeth and his gift of the gab earn him the title which St. John Chrysostom'southward preaching earned him: 'aureate-mouthed'.

Collected works

Widely used editions of Chrysostom's works are available in Greek, Latin, English, and French. The Greek edition, in eight volumes, was edited past Sir Henry Savile in 1613; the virtually consummate Greek and Latin edition is edited by Bernard de Montfaucon in xiii volumes, (Paris, 1718-1738) republished in 1834-1840). There is an English translation in the beginning series of the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers (London and New York, 1889-1890). A selection of his writings has been published more recently in French in Sources Chrétiennes.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 ane.one one.2 1.3 1.4 "St John Chrysostom" Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- ↑ Pope Vigilius, Constitution of Pope Vigilius, 553.

- ↑ Letters of Pope John Paul 2. Retrieved September three, 2021.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Walter Laqueur, The Changing Face up of Antisemitism: From Ancient Times To The Nowadays Twenty-four hours (Oxford University Printing, 2006, ISBN 0195304292), 47-48.

- ↑ Yohanan [Hans] Lewy, "John Chrysostom" in Encyclopedia Judaica (CD-ROM Edition Version 1.0), Ed. Cecil Roth (Keter Publishing House, 1997, ISBN 9650706658).

- ↑ The appointment of John'south birth is disputed. For a discussion meet Robert Carter, "The Chronology of St. John Chrystostom'southward Early on Life," in Traditio 18: 357–364 (1962)

- ↑ Jean Dumortier, "La valeur historique du dialogue de Palladius et la chronologie de saint Jean Chrysostome," in Mélanges de scientific discipline religieuse eight: 51–56 (1951). Carter dates his nascence to the year 349. See too Robert Louis Wilken, John Chrysostom and the Jews: Rhetoric and Reality in the Late 4th Century (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983), 5.

- ↑ "John Chrysostom," Encyclopedia Judaica (CD-ROM Edition Version 1.0), Ed. Cecil Roth (Keter Publishing House: 1997, ISBN 9650706658).

- ↑ The Encyclopedia Judaica describes Chrysostom's mother as a heathen. In Pauline Allen and Wendy Mayer, John Chrysostom, (Routledge, 2000), 5, she is described as a Christian.

- ↑ Robert Louis Wilken, John Chrysostom and the Jews: Rhetoric and Reality in the Belatedly Fourth Century (Berkeley: Academy of California Press, 1983, ISBN 978-0520047570), 7 prefers 368 for the date of Chrysostom's baptism; the Encyclopedia Judaica prefers the later appointment of 373.

- ↑ Wilken, 5.

- ↑ Philip Schaff and Henry Wace, (trs., eds.) Nicene and Mail-Nicene Fathers, Volume Two: Socrates and Sozomenus Ecclesiastical Histories (Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, reprint 1995, ISBN 1565631188), 399.

- ↑ Pauline Allen and Wendy Mayer, John Chrysostom (London; New York: Routledge, 2000, ISBN 0415182522), half dozen.

- ↑ John Chrysostom, In Evangelium Southward. Matthaei, hom. 50: 3-four: 58, 508-509.

- ↑ See Cajetan Baluffi, The Charity of the Church, trans. Denis Gargan (Dublin: Grand H Gill and Son, 1885), 39; and Alvin J. Schmidt, Nether the Influence: How Christianity Transformed Civilisation (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2001), 152; cited in Thomas Woods, How the Catholic Church Built Western Culture (Washington, DC: Regenery, 2005), 174.

- ↑ sixteen.0 xvi.one Wilken.

- ↑ David H. Farmer, The Oxford Lexicon of the Saints 2d ed. (New York:Oxford University Press, 1987), 232.

- ↑ Schaff and Wace, 149.

- ↑ 19.0 xix.1 St John Chrysostom the Archbishop of Constantinople. Orthodox Church in America. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- ↑ Scholasticus, "Chapter 18: Of Eudoxia'south Silver Statue", 150. Retrieved September iii, 2021.

- ↑ "John Chrysostom" in The Oxford Dictionary of Church History, ed. Jerald C. Brauer (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1971).

- ↑ "John Chrysostom" in Encyclopedia of Early Christianity.

- ↑ Lewy.

- ↑ Wilken, thirty.

- ↑ John Chrysostom, quoted in Wilken, 30.

- ↑ J.H.Due west.Chiliad. Liebeschuetz, Barbarians and Bishops: Army, Church building, and State in the historic period of Arcadius and Chrysostom (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990), 175-176.

- ↑ John Chrysostom, quoted in Liebeschuetz, 176.

- ↑ Wilken, 26.

- ↑ Thomas Woods, How the Catholic Church Congenital Western Civilization (Washington, DC: Regenery, 2005, ISBN 0895260387), 44.

- ↑ On the Priesthood was well-known already during Chrysostom's lifetime, and is cited by Jerome in 392 in his De Viris Illustrabus], affiliate 129

- ↑ See Wilken, xv, and as well "John Chrysostom" in Encyclopedia Judaica.

- ↑ Wilken, 15.

- ↑ "John Chrysostom" in Encyclopedia Judaica.

- ↑ Rodney Stark, The Rise of Christianity: How the Obscure, Marginal Jesus Motion Became the Dominant Religious Forcefulness in the Western Earth in a Few Centuries (Princeton University Press, 1997), 66-67.

- ↑ William I. Brustein, Roots of Hate: Anti-Semitism in Europe before the Holocaust (Cambridge Academy Printing, 2003, ISBN 0521773083), 52.

- ↑ "John Chrysostom" in Encyclopedia Judaica.

- ↑ "John Chrysostom" in Encyclopedia Judaica.

- ↑ John Chrysostom, Discourses Against Judaizing Christians (vol. 68 of Fathers of the Church), trans. Paul W. Harkins (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Printing, 1979), x.

- ↑ 39.0 39.ane Chrysostom, Discourses Against Judaizing Christians, xxxi.

- ↑ John Chrysostom, Hom. in Mt. xix,5: 57, 28.0.

- ↑ John Henry Newman, Chapter 2 The Newman Reader (Rambler, 1859). Retrieved September three, 2021.

- ↑ James Parkes, Prelude to Dialogue: Jewish-Christian relationships (London: Schocken Books, 1969), 153.

- ↑ Brustein, 52.

- ↑ Paul Johnson, A History of the Jews (New York: HarperPerennial, 1988), 165.

- ↑ Wilken, 124-126.

References

ISBN links back up NWE through referral fees

- Allen, Pauline and Wendy Mayer. John Chrysostom. Routledge, 2000. ISBN 0415182522

- Brustein, William I. Roots of Detest: Anti-Semitism in Europe earlier the Holocaust. Cambridge Academy Press, 2003. ISBN 0521773083

- Chrysostom, John. Discourses Against Judaizing Christians, trans. Paul W. Harkins. The Fathers of the Church, v. 68. Washington: Catholic University of America Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0813209715

- Farmer, David H. The Oxford Dictionary of the Saints, second ed. New York:Oxford University Press, 1987.

- Hartney, Aideen. John Chrysostom and the Transformation of the City. Bristol Classical Press, 2004. ISBN 0715631934

- Johnson, Paul. A History of the Jews. New York: HarperPerennial, 1988.

- Kelly, John Norman Davidson. Gilded Oral fissure: The Story of John Chrysostom-Ascetic, Preacher, Bishop. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995. ISBN 0801431891

- Laqueur, Walter. The Irresolute Face of Antisemitism: From Ancient Times To The Present Mean solar day. Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 0195304292

- Liebeschuetz, J.H.W.G. Barbarians and Bishops: Army, Church and Country in the Age of Arcadius and Chrysostom. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990. ISBN 0198148860

- Lewy, Yohanan [Hans]. "John Chrysostom." Encyclopedia Judaica (CD-ROM Edition Version 1.0). Ed. Cecil Roth. Keter Publishing House, 1997. ISBN 9650706658.

- Meeks, Wayne A., and Robert 50. Wilken. Jews and Christians in Antioch in the First Iv Centuries of the Common Era. (The Society of Biblical Literature, Number 13). Missoula: Scholars Press, 1978. ISBN 0891302298.

- Palladius, Bishop of Aspuna. Palladius on the Life And Times of St. John Chrysostom, transl. and edited by Robert T. Meyer. New York: Newman Press, 1985. ISBN 0809103583.

- Parkes, James. Prelude to Dialogue: Jewish-Christian relationships. London: Schocken Books, 1969.

- Schaff, Philip, and Henry Wace, (eds.). Socrates, Sozomenus: Church Histories. (A Select Library of Nicene and mail-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, second series, vol. 2). New York: The Christian Literature Company, 1890. ISBN 978-1565631168

- Stark, Rodney. The Rise of Christianity. How the Obscure, Marginal Jesus Motion Became the Dominant Religious Forcefulness in the Western Globe in a Few Centuries. Princeton University Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0060677015

- Stephens, W.R.West. Saint John Chrysostom, His Life and Times. London: John Murray, 1883.

- Stow, Kenneth. Jewish Dogs, An Imagine and Its Interpreters: Continiuity in the Catholic-Jewish Run across. Stanford: Stanford University Printing, 2006. ISBN 0804752818.

- Wilken, Robert Louis. John Chrysostom and the Jews: Rhetoric and Reality in the Tardily Fourth Century. Berkeley: Academy of California Printing, 1983. ISBN 978-0520047570

- Willey, John H. Chrysostom: The Orator. Cincinnati: Jennings and Graham, 1906.

- Woods, Thomas. How the Cosmic Church Built Western Civilization. Washington, DC: Regenery, 2005. ISBN 0895260387

External links

All links retrieved September 3, 2021.

- St. John Chrysostom Antiochian Orthodox Church

- St. John Chrysostom New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia.

- Was St. John Chrysostom Anti-Semitic? Orthodoxinfo.com.

| Preceded past: Nectarius | Patriarch of Constantinople 398–404 | Succeeded past: Arsacius of Tarsus |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia commodity in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Eatables CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-past-sa), which may exist used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of adequate citing formats.The history of earlier contributions past wikipedians is attainable to researchers here:

- John Chrysostom history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

- History of "John Chrysostom"

Note: Some restrictions may apply to employ of individual images which are separately licensed.

norrissdenard1995.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/John_Chrysostom

0 Response to "John Chrysotom Once Again She Calls for Johns Head"

Post a Comment